History has remembered the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 BC) as one of the greatest villains of antiquity. In 167 BC, he outlawed Judaism, desecrated the Jerusalem temple by sacrificing swine on its altar, and set up an image of himself in the guise of Zeus in its courts. His persecution was the culmination of the pressure that Hellenism was exerting over Judea at the time. This pushed conservative Jews to breaking point, and sparked the Maccabean Revolt. Under the leadership of Judas Maccabeus, the Jewish nation successfully overthrew Seleucid sovereignty and established a Jewish commonwealth that lasted a century until the arrival of Rome’s celebrity general, Pompey (63 BC).

As part of his program to control Judea and provide a better launching platform for operations against Ptolemaic Egypt, Antiochus constructed a fortress in Jerusalem. This fortress was known as the ‘Acra’, from the Greek word ἄκρα (akra), meaning ‘citadel’ or ‘summit’. The term is seen in the word ‘Acropolis’, which means ‘fortified city’ or ‘city on the summit’. 1 Maccabees 1.33–36 gives us this account of Antiochus’ construction of the Jerusalem Acra:

Then they fortified the city of David with a great strong wall and strong towers, and it became their citadel. They stationed there a sinful people, men who were renegades. These strengthened their position; they stored up arms and food, and collecting the spoils of Jerusalem they stored them there, and became a great menace, for the citadel became an ambush against the sanctuary, an evil adversary of Israel at all times.

The Acra, then, housed a garrison of Seleucid Greek soldiers, and their cache of weapons. It was approximately 250 x 60 m in area, and towered tall enough to provide a vantage point for all activities being conducted in the Jewish temple. Understandably, it was viewed by conservative Jews as a symbol of oppression.

The exact location of Antiochus’ Acra has been a subject of debate. If it afforded a good view into the temple courts, it would seem to have been located either to the immediate north or west of the temple. Yet nothing has been forthcoming in excavations and surveys.

But now, it seems, the riddle has been solved.

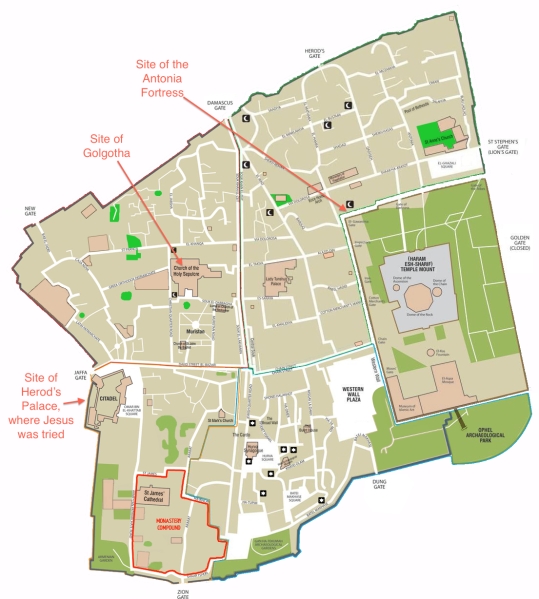

Archaeologists excavating in the Giv’ati Car Park in the City of David (just south of the Old City of Jerusalem) have uncovered what they believe to be the remains of the Acra fortress. While the ruins have been exposed for some time now, archaeologists have only recently been able to understand their configuration properly. They are now quite confident that they have indeed located the Acra. Furthermore, this makes complete sense of the reference in 1 Maccabees to its location in the ‘City of David’.

Excavations at the Giv’ati Car Park, Jerusalem—the location of the Acra.

The surprising thing about this is that the Acra was located on ground that was a good deal lower than the Temple Mount. Yet, we must realise that the Temple Mount in the second century BC was lower than its current level. The Second Temple was renovated on a monumental scale by Herod the Great (beginning in 19 BC), and he built the massive retaining walls that achieved the levels we can observe today. But before Herod’s renovation, the temple was most likely sitting at a lower altitude (albeit on the same spot). In any case, the Acra was located at a lower altitude. Therefore, it must have been quite an imposing tower to provide the garrison with its vantage point into the temple complex.

The Acra is a very significant find, as it dominated the landscape of Jerusalem at a critical time of its ancient history. It will be interesting to see if archaeologists can determine whether construction of the Acra in 167 BC compromised previous levels of occupation (‘strata’) from earlier historical periods.

What eventually happened to the Acra?

Judas Maccabeus was able to take Jerusalem and besieged the Acra in the course of his campaign. Yet the garrison managed to hold out for quite some time. With the Greco-Syrian soldiers watching on, Judas rededicated the temple in December 164 BC (or January 163 BC, depending on calendrical calculations). This was the origin of the festival of Hanukkah. Judas and his successors, his brothers Jonathan and Simon, managed to fortify Jerusalem effectively against the garrison, eventually winning complete freedom for the Jewish nation. Simon besieged the garrison and starved them out in 142 BC. Josephus tells us what Simon then did with the Acra in Antiquities 13.6.7:

He… cast it down to the ground, that it might not be any more a place of refuge to their enemies, when they took it, to do them a mischief, as it had been till now. And when he had done this, he thought it their best way, and most for their advantage, to level the very mountain itself upon which the citadel happened to stand, that so the temple might be higher than it. And, indeed, when he had called the multitude to an assembly, he persuaded them to have it so demolished… so they all set themselves to the work, and levelled the mountain, and in that work spent both day and night without any intermission, which cost them three whole years before it was removed, and brought to an entire level with the plain of the rest of the city. After which the temple was the highest of all the buildings, now that the citadel, as well as the mountain whereon it stood, were demolished.

Here’s a news clip with some good visuals of the excavations.

Here is Israeli archaeologist, Doron Ben Ami, speaking about the discovery of the Acra:

You can also read further articles on the discovery by clicking the following links:

http://greekcurrent.com/a-2000-year-old-greek-fortress-has-been-unearthed-in-jerusalem/