It’s sometimes claimed that the Old Testament forces a woman to marry her rapist, and that this demonstrates just how repugnant the Bible can be. The claim often forms part of an argument that seeks to disqualify the Bible from moral discourse in our modern world, or at the very least limit it.

Those wishing to defend the Bible against such a vile stance are often at a loss. There is sometimes an attempt to “soften the impact” by arguing that the laws do not deal with rape (non-consensual sex), but with seduction in which one partner brings the other around into consenting to sex.

Neither angle really grapples with the issues or the logic of the biblical data.

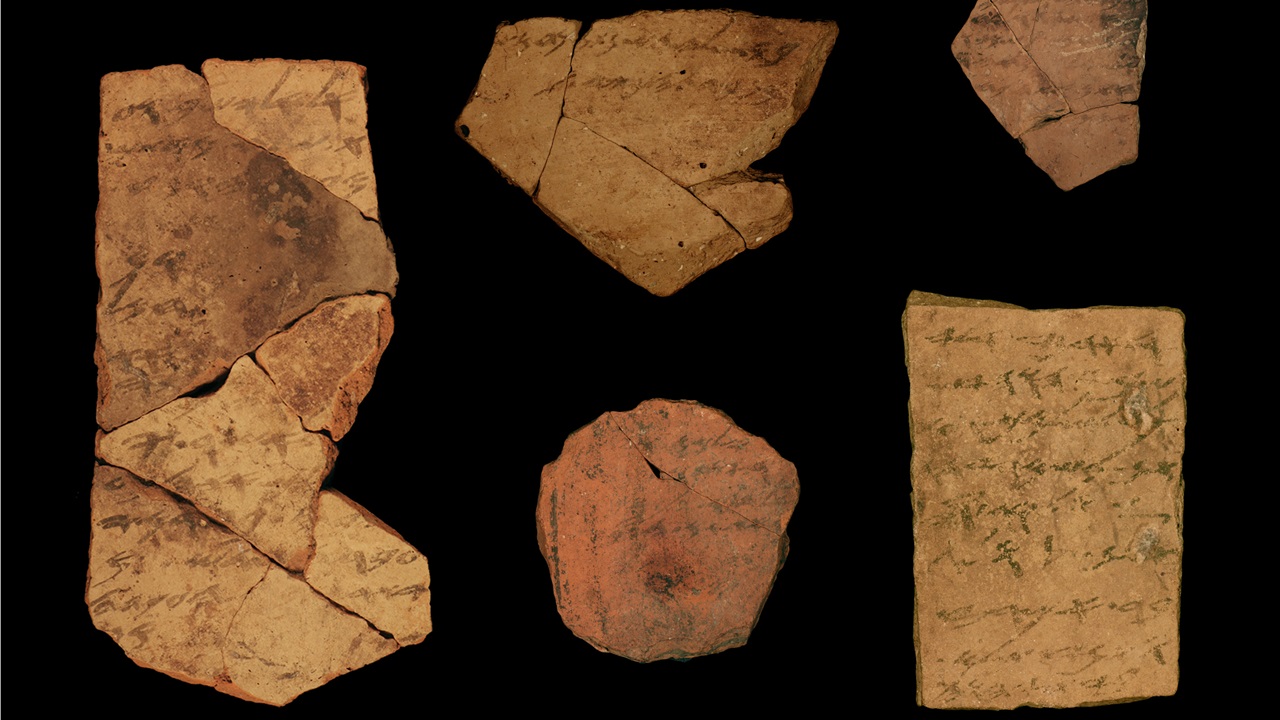

The relevant laws about sexual misconduct come from Deuteronomy 22:13–30. These laws deal with a range of circumstances, and rape is certainly among them (see below). The reference to “rape” is conveyed by the use of the Hebrew word תפש (tapas), which means “to hold onto” or “to hold down.” This is not a neutral word referring metaphorically to someone convincing another to their point of view, as perhaps a conniving seducer might convince a would-be partner to sleep with him. It is the language of violence, and it does not allow for consent. The word is used to describe the action of Potiphar’s wife on Joseph—not of her words to persuade him to sleep with her, but of her grabbing his clothing without his consent, and which he then had to abandon as he fled from her. She was not letting him go, forcing him to squirm out of his clothing and run off naked to escape her.

Nonetheless, the claim that the Bible forces a woman to marry her rapist is incorrect. It misunderstands the purpose and contours of the laws about sexual misconduct and, unfortunately, twists them into the rhetoric of misogyny.

It is important to understand the ancient context of these laws, as well as their casuistic nature—that is, they are not exhaustive legislation covering all eventualities, but scenarios from which one derives a range of principles to apply in various circumstances. There actually is considerable flexibility in these laws.

It is important to understand the ancient context of these laws, as well as their casuistic nature—that is, they are not exhaustive legislation covering all eventualities, but scenarios from which one derives a range of principles to apply in various circumstances. There actually is considerable flexibility in these laws.

The bottom line: the Bible does NOT force a woman to marry her rapist. Rather, it holds the rapist accountable for everything he’s got.

Here’s an excerpt from my commentary, Deuteronomy: One Nation under God (Sydney South: Aquila Press, 2016) dealing with the laws on sexual boundaries that are relevant to this issue (pp.260–71).

WARNING: The issues are both explicit and disturbing. Reading is for mature adults.

Sexual boundaries (22:13–30)

Deuteronomy 22:13 moves the discussion on to sexual boundaries. The connecting idea is once again a garment: the previous section finishes with regulations about garments, and the first scenario of improper sexual conduct here (22:13–19) likewise centres around a garment (22:17).

It is important to take all the laws in this section together, as isolating them from each other can lead us to [p. 261] grossly misconstrue their intent. When read in isolation, some of these laws appear repugnant and immoral to our modern sensibilities. However, when we interpret them within the context of the wider section, Deuteronomy’s wider concerns, as well as the ancient historical context, we see how these laws do have proper ethical intent. We must remember that these laws are given in casuistic form, rather than comprehensive legislative clauses. The various scenarios invite comparison with each other, which is how they give us the necessary leverage for inferring the ethical principles and purposes that they represent.

The first two scenarios (22:13–19 and 20–21) deal with perceived sexual misconduct and the issue of virginity. The next four scenarios (22:22, 23–24, 25–27, and 28–29) deal with adultery and rape, while the final scenario (22:30) deals with incest. Let’s deal with each in turn.

The first scenario (22:13–19) sees a man marry a woman, but when he goes to sleep with her believes that she is not a virgin. The issue of crossing boundaries is seen in the way the Hebrew here expresses the sexual act. It uses expressions such as the man ‘coming into’ the woman (22:13), or ‘coming near to’ her (22:14). This implies both entry into a private room, as well as the intimacy of sexual penetration. The implication is that sex breaks down the boundary between two people to unite them as a single unit.

The issue of virginity is a critical one. The law focuses on the woman’s virginity rather than the man’s here because the woman is the one who carries and bears children. The lack of comment on male virginity should not be construed as men having freedom to ‘sleep around’, while women do not. In fact, the need for female virginity prior to marriage and the prohibition of adultery (5:18) imply the need for male virginity prior to marriage also. If a woman is found to have lost her virginity prior to marriage, it is possible that someone other than the man she has married has fathered her children. This compromises the identity and cohesion of a family, and blurs lines of familial responsibility and inheritance. The accusation of such [p.262] promiscuity is very serious, so evidence needs to be produced in line with the covenant’s principle of objectively establishing the facts behind any charge.

In this case, the evidence produced by the woman’s parents is a cloth (22:17). Presumably this is a sheet on which the newly married couple slept together, showing evidence of bleeding from the stretching or tearing of the woman’s hymen during intercourse. Of course, this raises the question of what would happen if the woman’s hymen did not tear during intercourse, or if it had torn before marriage through innocent, mundane activity. Again, the casuistic nature of this law must be borne in mind. The law demonstrates one example from which a larger principle is to be inferred. As such, the law does not limit the admissible evidence to a bloodstained bed sheet. Other evidence may certainly be brought forward in the woman’s defence. Furthermore, when we remember that no capital charge could ever be successful without the confirmed testimony of two or three witnesses (17:6), we realise how difficult it would be to prove the case against the woman here. If the woman or her family were unable to produce any forensic evidence of her virginity, her guilt is not thereby assumed. In line with 17:6, there must be positively corroborated evidence that the woman had indeed been wilfully promiscuous. This is why this scenario must also be read in conjunction with those that follow, for they present other cases of sexual misconduct that affect the interpretation of this law. These other cases demonstrate, for example, that this law could not convict a woman who has been raped, for although she is no longer a virgin, she herself is innocent of misconduct. A woman is not to be blamed for being a victim (see also below). This law also does not deal with a woman who had been previously married and, therefore, would no longer be a virgin on her second marriage. The casuistic nature of this law means that it presents a very specific example from which wider implications must be interpolated.

While this law obviously prohibits women from engaging in sexual promiscuity, it also shows that no man may simply [p.263] use a woman for sexual gratification and then abandon her. On the contrary, sex is put in the context of permanent committed relationship. Casual sex is, therefore, not an option for anyone—male or female—and neither is casual divorce. Accordingly, if the man’s accusation against the woman fails, and indeed it would be impossible to convict her of promiscuity without the verified testimony of two or three witnesses, the man is punished (22:18), and his right to divorce the woman is revoked (22:19). In addition, he is required to pay damages for defaming the woman through his accusation. This law, therefore, aims to enshrine sex within marriage, and also promote sober attitudes towards sex among both men and women.

We may be tempted to see the revoking of the man’s right to divorce here as unnecessarily harsh on the woman, who seems to be given no choice in the matter. However, this is not the case. The law does not say the woman is unable to divorce the man. The right is only denied to the man in this scenario. Furthermore, the principle being demonstrated is that divorce is never to be entertained lightly. We must also bear in mind the situation of women in the ancient world. There was no public education or widespread literacy; no housing options, employment opportunities, or social security; no police, charities, clubs, or other social infrastructures that might allow women in the ancient world to live independently. This is why women and children were particularly vulnerable in the ancient world. They depended on being attached to a family unit headed by a man who could physically protect and provide for them. For a woman, this began with the household of her father. When she was of age to bear children, she would join the household of her husband, and become firmly established within the family line by providing it with children. If she outlived her husband, she would hopefully join the household of one of her sons. Unlike today, therefore, bearing children was not merely a matter of personal choice for a woman. It was vital for her livelihood [p.264] in a relatively undeveloped society.[1] Thus, this law is not denying the woman any rights, but rather ensuring that she is adequately protected for the rest of her life. It preserves her opportunity to bear legitimate children who will inherit from their father, especially in the face of false accusations that imperil that opportunity, and gives her ongoing access to a husband’s resources.

Scenario 2 (22:20–21) sees the charge against the woman’s virginity proved true. As implied by 17:6, this means that the case has been proved beyond reasonable doubt by the corroborated evidence of two or three witnesses. In that case, the death penalty is exacted on her. This raises the issue of what is done to the man who had taken her virginity, which this scenario does not deal with. However, this is not an exoneration of that man. Taken in isolation, this law might be interpreted as privileging patriarchy and male domination. On the contrary, though, the scenarios that follow demonstrate that a man involved in illicit sex is also subject to the death penalty. Again, this is why it is important to take all the scenarios in this section together, rather than in isolation. Together, these scenarios provide a fuller understanding of sexual ethics in ancient Israel.

Scenario 3 (22:22) is a plain case of adultery. If a man sleeps with a married woman, both he and the woman are put to death. This is simply an expansion of the seventh of the Ten Points (5:18). Note that there is no statement about the man’s marital status here. It is irrelevant to the charge, because the law defines adultery around a married woman. It is the biology of procreation that drives this definition. If a man sleeps with two women and both fall pregnant, there is no doubt about the paternity of the children. This is partly why the law permits an Israelite man to take more than one [p.265] wife (cf. 21:15–17) and for this not to be viewed as adultery.[2] However, if a woman sleeps with two men, there is doubt about the paternity of her children, which damages family cohesion, as well as lines of kinship and inheritance. Adultery, therefore, is the situation in which a married woman sleeps with a man who is not her own husband. Both the woman and the man involved in this illicit act are to be purged from the Israelite community.

Scenario 4 (22:23–24) deals with a man sleeping with a woman who is betrothed to another man. The incident is placed within a town (22:23). This, in part, is how we see boundaries as the structuring principle of this law: the incident occurs within ‘city limits’, so to speak, in contrast to Scenario 5 that follows. The point of this is to demonstrate that if the man were sexually assaulting the betrothed woman, she could scream and be heard by others in the town. The fact that she does not scream in this scenario suggests she has consented to intercourse, so that both she and the man who sleeps with her are guilty of sexual misconduct. The critical issue here is that the woman is betrothed to another man, so that the paternity of her children is placed in doubt by her conduct. Therefore, as in the previous case (22:22), both the man and the woman are executed when proved guilty.

Once again, it is important to remember the casuistic nature of this scenario, which does not exhaust all possibilities. For example, the scenario does not deal with a man assaulting a woman and preventing her from screaming. A man might, for instance, take a knife to the woman’s throat, or have her gagged as he attacks her. In this case, one can hardly expect the woman to scream and attract attention. Therefore, it would be a gross miscarriage [p.266] of justice to condemn her to death for not doing so. But Scenario 4 here does not condemn a woman merely for not screaming. That would be to misinterpret its purpose. On the contrary, the lack of screaming in this particular scenario is indicative of the woman’s consent to intercourse with a man to whom she is not betrothed. Consent is demonstrably the critical factor. This scenario presents a typical example to establish a legal norm, rather than an extreme example to determine legal limits (that comes in Scenario 5). Consent, not a lack of screaming, is a major consideration in cases of sexual misconduct. Both the man and the woman in Scenario 4 engage in consensual intercourse, and both are guilty of sexual misconduct, because the woman is betrothed to another man.

Scenario 5 (22:25–27) presents the important counterbalance to Scenario 4. In Scenario 5, the betrothed woman is clearly assaulted, but this occurs in the countryside—outside the city boundary. This location sets up an extreme situation to contrast directly with the previous one: the woman here screams, but she is too far away for anyone to hear her and come to her aid. As in Scenario 4, screaming is the cipher for the issue of consent. While the woman in Scenario 4 consents to intercourse, the woman in Scenario 5 clearly does not. Therefore, the law does not condemn the woman in Scenario 5 in any way (22:26). She is an innocent victim.

There are a number of important factors to unpack here. First, the woman in Scenario 5 is not blamed in any way for the attack upon her. It does not, for example, blame her for dressing a particular way, flirting, or otherwise leading the man on. These do not even enter consideration. The blame for the assault is laid solely upon the man who attacked her. This shows that sexual assault is never deemed an acceptable response to anything. The perpetrator can never blame the victim for provoking him. Therefore, the victim is always innocent and assault is never condoned. Second, the law does not see rape as a subcategory of adultery. Rather, 22:26 equates rape with murder. This acknowledges the profound impact that rape has: it imposes a kind of living death on the [p.267] victim. Third, equating rape with murder shows not only the enormity of the crime, but also the magnitude of the healing required after it. For the victim, the path to restoration is akin to a resurrection. Rape is not something a victim can just ‘get over’. The victim requires significant and sustained care. There is even the possibility that the victim will never fully recover from the psychological scars inflicted on her. As such, the man in Scenario 5, to whom she is betrothed, becomes a very important figure. He is able to marry her and provide her with ongoing care, protection, and provisions within the context of a permanent committed relationship.

This final factor helps to explain the logic at work in Scenario 6 (22:28–29). This scenario is identical to Scenario 5 with one key difference: the woman is not betrothed. When such a woman who has not been spoken for is raped, the penalty on the perpetrator changes. He is not put to death, but rather is forced to marry the woman without the option of ever divorcing her, and he must pay a fine of fifty silver shekels to the woman’s father.

To our modern sensibilities, the outcome of Scenario 6 sounds preposterous, as it appears to commit a victim permanently into the hands of her assailant. However, this is most certainly not the intent, and also why we must read this scenario in tandem with the others that precede it. As we have seen, ancient societies were relatively undeveloped, and so lacked the necessary infrastructures that could allow women to live independently. It simply was not an option at that time. As such, the perpetrator in Scenario 6 is given a stay of execution, not because he is less guilty than the perpetrator in Scenario 5, or because the unattached woman is somehow less valuable than the woman who is spoken for. Far from it! The perpetrator is allowed to live so that he provides economically for the victim for the rest of his life. This is why he is refused the right to ever divorce her. It ensures that his victim has complete access to all his resources for her own wellbeing for the rest of her life. It is the closest thing the ancient world had to suing someone ‘for all they’ve got’.

[p.268] There are a few further points to state about this situation. First, this scenario employs what we might term a retrieval ethic. It recognises that the crime against the woman deserves the severest penalty under the Law: death. However, in this case, carrying out the severest penalty might leave the woman destitute. She is not betrothed to any man, and there is a strong likelihood that another man would not take her in marriage, or that she herself might not wish to marry anyone. Since women were so vulnerable in the ancient world without male protection and provision, this potentially imperilled the woman. Rather than make her suffer further, in addition to the consequences of rape, this law seeks to mitigate her plight by ensuring economic compensation for her in perpetuity, as well as the opportunity to bear children who might care for her in her old age. Bearing children provided women with security in the midst the rigours of ancient life. The perceived lenience towards the assailant here is actually designed to retrieve the situation in some measure for the victim.

Second, although this law states the perpetrator must marry the victim without recourse to divorce, it does not force the victim to marry him. In fact, a woman in this situation may legitimately refuse to marry her attacker. To us this might seem a more suitable outcome, as it would remove a woman from the vicinity of her attacker. But it seems so to us largely because of the many options for independence available to women today. Such options simply did not exist in the ancient world. So even though this law does contain such flexibility, the extreme vulnerability of women in the ancient world meant that it could inadvertently compromise a victim’s long-term wellbeing and standing.

We see this demonstrated in 2 Samuel 13, where King David’s son, Amnon, rapes his half-sister, Tamar. After the assault, Tamar begs Amnon not to send her away (2 Samuel 13:16), using the basic language associated with divorce. By sending her away, Amnon was potentially consigning her to a life without the possibility of marriage and, therefore, a life outside the protection of a family or clan structure. This [p.269] was more than just a life lacking opportunity. It could result in life-threatening poverty and exploitation. Tamar’s fear of destitution is, therefore, palpable. Amnon, however, callously throws her out after assaulting her, leaving her vulnerable. Fortunately for Tamar, her brother, Absalom, becomes her protector and provider. However, because Tamar is not betrothed, and Amnon does not marry her, she is denied the opportunity to entrench herself within a family by contributing children who might also care for her in old age. As such, the text describes Tamar’s fate as ‘desolate’ (2 Samuel 13:20).

Tamar’s situation also highlights some of the other outcomes that might arise from an assault like that in Scenario 6. For example, a rape victim’s male relatives—her father, a brother, or a nephew—might plausibly provide her with ongoing care. The logic in the cluster of scenarios here in Deuteronomy 22 means that in such situations, the attacker would most likely be executed, in line with the severity of the crime.[3] While this may seem a preferable outcome to our modern sensibilities, it also confines the victim to the margins of family life. It deprives her of a woman’s most fundamental contribution to ancient society, which also ensured her wellbeing: childbearing within a family.

This cluster of scenarios demonstrates how vulnerable women in the ancient world were. Ultimately, there was no ‘good’ outcome for a rape victim, for she was inevitably at some disadvantage that could not be undone. This highlights the importance of the final of the Ten Points (5:21), which enjoins people to live responsibly, rather than in the unbridled pursuit of pleasure, power, or gain. People were to treat others with dignity and respect in accordance with nature and circumstance, recognising the impact of their actions on others. This promotes both self-awareness and [p.270] social awareness more broadly. Men in particular, as the powerful of society, were to use their power in the responsible service of others to build a cooperative and safe society. They were not to treat women as objects for self-gratification or personal gain, and relationships were not to be trifled with. Sex, with its procreative power, was not to be treated casually or abusively, but within the context of ongoing committed familial relationship. The normative place for sex was within marriage, which provided a natural institution for the nurture of family. Rape is never condoned, but is equated with murder. These scenarios show that a rapist must always be held responsible for the crime, the victim is never to be blamed, and the ongoing wellbeing of the victim is of the utmost importance. These laws aim to prevent the abuse of power, protect and provide for the vulnerable, and protect family life as the basic dynamic at the heart of society.

This section closes with an apodictic law prohibiting a man from marrying his father’s wife (22:30). The woman in question is not described as the man’s ‘mother’. This means the law has a broad application to any woman who was married to the man’s father, such as a second wife or a concubine, as well as the man’s own mother. By using the language of marriage (literally, ‘taking’), the law extends the prohibition on such sexual relations even beyond the time of the father’s death, for a woman could not be married to both a father and his son at the same time. This law distinguishes Israel from some of its neighbouring cultures, such as Assyria and pre-Islamic Arabia, which permitted a man to marry his stepmother after his father’s death. The rationale for the law is that such a relationship represents a crime against the father, even though he may be dead. The implication is that any woman married to a man’s father became kin—a status that endured beyond the father’s death, thus making any relationship with her incestuous. This also represents a clear boundary between the generations within a family. If a man married his stepmother, the children of their union could be considered both the [p.271] children and step-grandchildren of the woman, resulting in relational confusion. Thus, while the six scenarios before this law deal with respecting the relationships of peers, this law extends relational integrity across the generations by drawing a clear boundary between them.

[1] Sterility also had a profoundly tragic influence over a woman’s long-term livelihood. This dynamic that saw a woman’s survival attached so closely to her childbearing ability may also stand behind the statement in 1 Timothy 2:15.

[2] Another reason that the Law allows Israelite men to take more than one wife is that men were usually physically strong enough to provide physical protection and sustenance to women and children in what was an undeveloped society. Men, though, had to provide amicably and equitably for their compound families (see Deuteronomy 21:15–17).

[3] To that end, we note that Tamar’s full brother, Absalom, who took her into his care, eventually kills Amnon for the rape (2 Samuel 13:28–29).

You can purchase Deuteronomy: One Nation under God HERE, or the Kindle version HERE.

Genesis 3 tells a story of woe in idyllic paradise. After the sneaky snake tempts the woman, both she and the man eat fruit from the tree that Yahweh God had forbidden to them. Consequently, the couple now find themselves with the stark realisation of their nakedness, and dread over what the deity will think of them. And so, when they hear his steps in the garden which they are supposed to tend, they hide in fear and shame.

Genesis 3 tells a story of woe in idyllic paradise. After the sneaky snake tempts the woman, both she and the man eat fruit from the tree that Yahweh God had forbidden to them. Consequently, the couple now find themselves with the stark realisation of their nakedness, and dread over what the deity will think of them. And so, when they hear his steps in the garden which they are supposed to tend, they hide in fear and shame. With hardship will you eat of it

With hardship will you eat of it

Richard Dawkins reflects this kind of scenario when he questions the character and justice of God. He asks, quite perceptively, why it is necessary for the God of the Bible to send his Son to die a bloody death for sin. Why could God simply not forgive sins with a wave of his hand, as it were? Can’t God just simply waive the penalty and move on?

Richard Dawkins reflects this kind of scenario when he questions the character and justice of God. He asks, quite perceptively, why it is necessary for the God of the Bible to send his Son to die a bloody death for sin. Why could God simply not forgive sins with a wave of his hand, as it were? Can’t God just simply waive the penalty and move on? This is why the cure for sin requires the Incarnation. It takes God himself to become a human being—the image of God—and so redefine human nature. Christ is the new Adam—the one who fixes human nature and relates rightly to God. It is Jesus’ entire human life that is redemptive—not just his death and resurrection. He overcomes the devastation of human nature, which every human suffers. And because of humanity’s place as God’s image over all creation, the redemption of human nature entails the redemption of all creation.

This is why the cure for sin requires the Incarnation. It takes God himself to become a human being—the image of God—and so redefine human nature. Christ is the new Adam—the one who fixes human nature and relates rightly to God. It is Jesus’ entire human life that is redemptive—not just his death and resurrection. He overcomes the devastation of human nature, which every human suffers. And because of humanity’s place as God’s image over all creation, the redemption of human nature entails the redemption of all creation.

One method popularly espoused is to divide the Law into three categories: (1) civil laws pertaining to the life of Israel as a national entity in ancient times; (2) ceremonial laws pertaining to how Israel worshipped God at the tabernacle or temple; and (3) moral laws that indicate the ethical standards God desires of people. Under this scheme, the civil and ceremonial laws are seen as no longer applicable to Christians, because they are fulfilled in Christ. The moral laws, though, do continue to have force, since God’s standards have not changed. It therefore takes Jesus’ fulfilment of the Old Testament and the high ethical standards of believers quite seriously.

One method popularly espoused is to divide the Law into three categories: (1) civil laws pertaining to the life of Israel as a national entity in ancient times; (2) ceremonial laws pertaining to how Israel worshipped God at the tabernacle or temple; and (3) moral laws that indicate the ethical standards God desires of people. Under this scheme, the civil and ceremonial laws are seen as no longer applicable to Christians, because they are fulfilled in Christ. The moral laws, though, do continue to have force, since God’s standards have not changed. It therefore takes Jesus’ fulfilment of the Old Testament and the high ethical standards of believers quite seriously.